Digital Advertising

Recent news reports suggest Google is considered a monopoly. What are the implications of this for advertisers?

Copyright© Schmied Enterprises LLC, 2025.

Link of the day.

Business Insider: You.com CEO Richard Socher on Google's search monopoly (March 2025). Here.

Link of the day.

Google Cloud for Startups application page. Here.

Link of the day.

Website for the former Mayfield AI (creators of the Kuri robot). Here.

Link of the day.

C3 AI - Enterprise AI solutions. Here.

Link of the day.

Escape Campervans rentals. Here.

Imagine arranging Google's advertising customers along a curve, ordered from the highest spenders to the lowest. Each point on this curve represents an advertiser's spending level on Google Ads.

Naturally, advertisers expect a return on their investment over time. High spenders, such as large corporations like Coca-Cola, often focus on brand marketing. Their goal is to maintain brand awareness among their target audience, leveraging revenue primarily from existing customers.

Conversely, other customers, like startups and small businesses, might initially spend more on advertising than they immediately recoup from new customers. Their strategy is often speculative, relying on repeated business and the eventual profitability derived from the customer's lifetime value (CLV).

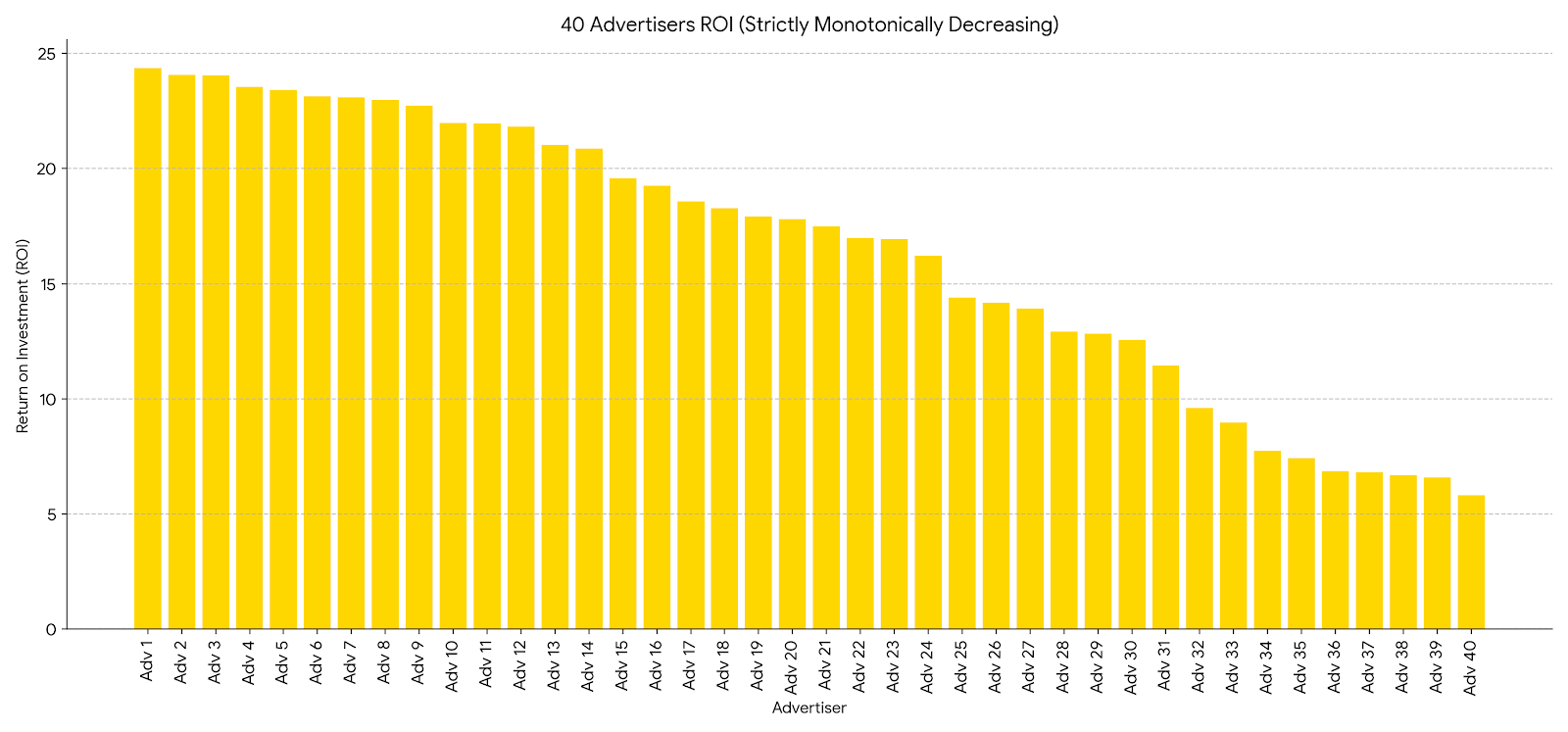

Now, let's modify this curve by plotting the ratio of Customer Lifetime Value (CLV) to ad spending for each advertiser. The advertisers at the top of this revised curve achieve a high yield on their spending. In contrast, the 'long tail' of the curve often represents more speculative spending or brand-focused marketing where immediate returns are lower relative to the amount spent.

How do advertising platforms like Google or Facebook operate within this market dynamic?

Advertising spending is typically rational, guided by available budgets and the potential return based on CLV. Marketing providers strive to meet advertiser needs, primarily by ensuring ad relevancy. Advertisers insist on showing ads to potential customers who are likely to be interested. This focus on relevance creates a close alignment, or 'fit,' between the provider's targeting capabilities and the advertiser's goals. For instance, Google displays ads alongside relevant search queries, while Facebook might place them within relevant user feeds or groups.

This targeting process influences the advertiser distribution curve discussed earlier. Compared to randomly assigning ad slots, targeted advertising might shift the curve, potentially favoring either high-spending brand advertisers or the long tail of smaller, performance-focused challengers. Inevitably, some advertisers might find fewer relevant, high-performing slots available. They face a choice: continue spending on less effective placements (reducing their return on investment) or seek alternative advertising channels.

Advertisers might initially explore less targeted channels, perhaps similar to advertising on survey platforms, as a potentially cost-effective way to test market interest. This approach can sometimes be cheaper than highly targeted platforms.

Following initial testing, advertisers might transition to major platforms like Meta or Google for more structured paid media campaigns. They can manage campaigns manually or utilize the platform's automation features. Typically, it takes some time, often around a week, for performance data to stabilize and reveal the actual return on investment (ROI). If the ROI is positive, advertisers may increase spending. However, effectiveness can diminish over time as ads are repeatedly shown to the same users, including existing customers or those who have previously seen the ad but shown no interest, leading to ad fatigue.

When returns diminish on one platform, advertisers may explore other channels. This creates opportunities for different ad networks and platforms such as MediaVine, Media.Net, or Taboola.

Several factors contribute to Google's dominant market position, often described as monopolistic. They possess vast amounts of user data, enabling sophisticated targeting. Owning the Chrome browser and influencing web development and advertising standards gives them significant control over how ads are delivered. This market power allows them to potentially charge higher prices. The resulting revenue can fund extensive research and development in areas like artificial intelligence, computer architectures, and semiconductors. Similarly, Meta invests heavily in areas like augmented reality hardware. Theoretically, competitors could undercut these giants by focusing solely on selling traffic at a lower cost, without such extensive R&D investments. However, a major challenge is overcoming the powerful network effects these large platforms enjoy; acquiring a critical mass of users is an expensive undertaking.

New advertising providers might find opportunities by monetizing platforms with fewer inherent network effects, such as email marketing or in-app advertising within personal productivity software available in app stores. By offering viable alternatives, they could potentially reduce the demand for advertising on Google and Facebook (effectively duplicating A demand curve to the left of those dominant platforms). This creates space in the market for lower-cost ad services catering to the remaining or underserved demand. Even large advertisers might allocate a small portion of their budget (e.g., 1%) to test alternative providers and gather comparative performance data, such as click-through rates (CTR).

Success for competitors hinges on differentiation and achieving a strong product-market fit. For instance, Bing's difficulty in gaining significant market share against Google is partly attributed to its strategy of closely mimicking Google's features rather than offering distinct advantages. This lack of clear differentiation, combined with Google's network effects, created an opening for platforms like Facebook, which differentiated by focusing on advertising within social connections and personal channels. Microsoft later pursued a differentiation strategy through professional networking by acquiring LinkedIn.

So, what strategies can advertisers employ? Consider this simplified scenario using arbitrary numbers: Suppose an advertiser spends $100 on ads, generating one million impressions and driving one hundred thousand visitors to their website. If this advertiser *only* monetized their site by displaying third-party ads (perhaps from the same ad provider), they might earn only $10. However, the advertiser's primary goal is usually to sell their own products or services. By investing in improving their website design and services, they encourage customers to return. If effective, this could lead to a scenario where each customer returns multiple times (e.g., fifteen times on average), ultimately generating $150 in lifetime value from the initial $100 ad spend. This positive gross profit allows for reinvestment in growth until the potential customer base becomes saturated.